|

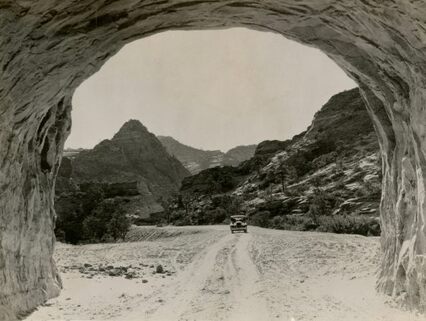

How a backroom deal gave Utah its second national park This summer will see the centennial of Bryce Canyon National Park, one of the most popular travel destinations in America. This year alone, nearly two million people will stand at its airy, pine-bedecked rim and gaze out over a land of intricately eroded pinnacles and plunging canyons, all displayed in colors that defy description. Quite a few will venture down one or more of the park's many hiking trails, which afford close-up glimpses of Cenozoic geology at its weirdest. Some may give thanks that this marvel of Earth sculpture was set aside in 1923 for all of us—indeed, the whole world—to enjoy. I would wager, though, that very few of these visitors will have heard of Bryce’s complicated backstory. Bryce Canyon became a national park only through an intricate set of negotiations which took place over a span of years during the 1920s. These involved one of the nation’s largest railroads, the State of Utah, the federal government, and a young Mormon couple from the nearby town of Panguitch, who happened to hold the key to some of the most scenic real estate in southern Utah. The story goes back to 1896, when Utah gained statehood. As with other western states, this came with a gift package from Uncle Sam: hundreds of square-mile sections of federal public domain, granted to the state as a means of obtaining revenue. One such section happened to lie right at the rim of the Paunsaugunt Plateau, in what would later become Bryce Canyon National Park. It was on this land that Reuben and Minnie Syrett, an enterprising local couple who had homesteaded a plot of grass and sagebrush a few miles to the north, erected a rustic lodge and some cabins to host visitors who wanted to sample the views from the rim of Bryce Canyon. Opened in 1920, their lodge featured a homey atmosphere and a pine tree growing right through the porch roof. They called it Tourist Rest. A friend advised the Syretts to obtain a long-term lease to the state land they were using, which took the couple several years to arrange. By then a much bigger outfit was eyeing the tourism potential at Bryce’s rim. The Union Pacific Railway, which operated a transcontinental rail line through northern Utah, was looking to grow its tourism business in the southern part of the state. Congress had just established Zion and Grand Canyon as national parks, prompting the UP to acquire a spur line to Cedar City, a day’s drive from Zion and a couple days from the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. The railroad set up a subsidiary called the Utah Parks Company to build and operate tourist lodges at these locations, as well as provide transportation from Cedar City. The rim of Bryce Canyon offered an ideal spot for another such lodge. First, though, the UP needed to acquire the land which the Syretts were using for their Tourist Rest. Reuben and Minnie rejected several lowball offers from the railroad, finally accepting $10,000 for their property and a valuable water right. This enabled them to relocate their operation to their homestead just a few miles away. In exchange, the railroad gained ownership of almost 22 acres of prime real estate right next to the rim, where it immediately started to build a much larger and more elegant lodge. By this time the federal government was taking a keen interest in Bryce Canyon. In 1920 Horace Albright, the number two man in the National Park Service, paid a visit to Bryce and came away convinced that this should become a new national park. At the time, Bryce Canyon was under the control of the U.S. Forest Service, but Albright believed that a scenic wonder of such magnitude belonged in the national park system. Albright had enough friends in Washington to make the transfer to his bureau possible. On June 8, 1923, President Warren Harding signed a proclamation creating the Utah National Monument, taking in just over 7,000 acres of the rim area and the scenic badlands below the rim. Most everyone in Utah, from businessmen in Panguitch to the governor and the state’s congressmen, wanted Bryce Canyon to be a national park. But the Union Pacific’s property, along with the rest of the square mile section that the State of Utah still controlled, presented a significant hangup. Horace Albright was not interested in a national park with a large hole in the middle of it. Harding’s proclamation, moreover, specified that Bryce would become a national park only after this land had been acquired, which left Albright and the Park Service with every incentive to conclude a deal with the railroad. In July 1927 (as detailed in Nicholas Scrattisch's excellent historical report, prepared for the Park Service in 1985), Albright sat down with Union Pacific President Carl Gray at the elegant Canyon Hotel in Yellowstone National Park, where Albright served as superintendent. Gray offered Albright a deal: the UP would turn over its property at Bryce Canyon, along with its lease interest in the remaining state land, in exchange for a promise to have the federal government build a new highway from Zion National Park to U.S. 89, twenty-four miles to the east. Why was the Union Pacific so interested in a highway? The answer has to do with the then-popular idea of “circle tours” – paid motor coach excursions from one national park to another, with stops at fine lodges along the way. The Utah Parks Company offered just such a tour: a five-day trip out of Cedar City, taking in Zion, the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon, and Cedar Breaks, a small but colorful section of cliffs just east of Cedar City. But getting from Zion to the North Rim involved an arduous two-day drive through the windswept desert of northern Arizona, then another long drive north to Bryce Canyon. Tourists wanted to see the sights, not sit all day in a motor coach on dusty roads. Carl Gray wanted to shortcut this route with a new highway from Zion to the village of Mt. Carmel, where its drivers could either turn south to the Grand Canyon or head north to Bryce Canyon. But to build such a highway would require tunneling through a 400-foot-high cliff at the eastern edge of Zion. There was no way the UP was going to pay for such a monumental project, but perhaps the government in Washington would. Horace Albright felt it could be done, and the deal was reached. It was an unprecedented accommodation of a private interest by the federal government, but Albright believed that in the end, it would serve the public to have an easier highway connection between Zion and Bryce Canyon. The deal removed the last obstacle to Bryce Canyon gaining national park status. Congress approved the necessary legislation, which President Hoover signed on September 15, 1928. Its name was changed to Bryce Canyon, replacing the parochial Utah National Monument.  Approaching the second, shorter tunnel on the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway. Photo by Homer Jones, Bureau of Public Roads, courtesy National Archives Approaching the second, shorter tunnel on the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway. Photo by Homer Jones, Bureau of Public Roads, courtesy National Archives The Bureau of Public Roads undertook at once to construct the Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway, with its amazing mile-long tunnel which plowed right through the sandstone cliff above Zion’s Pine Creek. Opened in a gala celebration on the Fourth of July, 1930, the route quickly became an attraction in itself. You can imagine the excitement of the first motorists to go through this tunnel, where enormous gallery windows gave a dizzying view into Pine Creek canyon. Today, the deal that Horace Albright struck with Carl Gray and the Union Pacific Railway would be subject to much more scrutiny. At the time, though, it was deemed to serve the public interest, and perhaps it did. But what about Reuben and Minnie Syrett? After being forced to give up their Tourist Rest at the rim of Bryce Canyon, they started a new venture on their old homestead, right at the entrance to the new national park. Ruby’s Inn grew to become the largest resort in south-central Utah and the region’s major employer. This hard-working couple and their successors, as much as the Union Pacific Railway, became the beneficiaries of America’s love affair with its national parks.

For more Bryce Canyon history, see my book Wonders of Sand and Stone. Sources: Williams, Kendall Hughes. The Syrett Family: from Buckinghamshire, England to Utah to Ruby’s Inn, Utah, 1606-2006. Edited by Roderick K. and Kathern Syrett. Salt Lake City: Price & Associates, 2006. Scrattish, Nicholas. “Historic Resource Study, Bryce Canyon National Park.” Denver, CO: US Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Regional Office, Branch of Historic Preservation, 1985, http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/elusive_docs/46.

0 Comments

|

AuthorI've been exploring parts of the Colorado Plateau for a half century, and in that time I've come to appreciate the legacies of those who loved and cared for this landscape long ago. In this blog I'll delve into a few of their fascinating stories. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed