Excerpt from Wonders of Sand and Stone

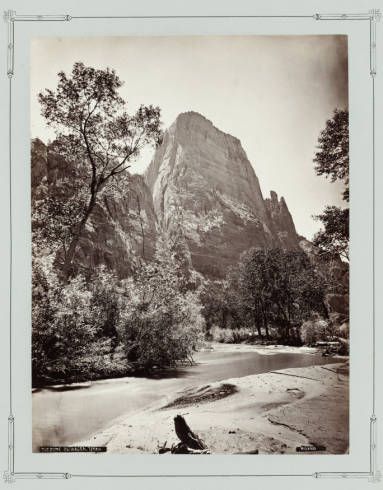

Zion Canyon as photographed in 1871 by Jack Hillers of the Powell Survey

Zion Canyon as photographed in 1871 by Jack Hillers of the Powell Survey

From Chapter 6: “Desert Yosemite”:

More than a century ago, the great canyon of the North Fork of the Virgin River spoke wonders to scientists, travelers, and local inhabitants alike. If their reasons for coming to this canyon differed, each found a unique splendor in its towering sandstone cliffs and fern-lined grottoes. Named Mukuntuweap by John Wesley Powell, and called Little Zion by its Latter-Day Saint settlers, the canyon’s walls enclosed scenes of intimate beauty. Graceful cottonwoods lined the river bottom, keeping the summer heat at bay, while delicate vegetation ringed dripping springs and plunge pools. Zion Canyon was said to surpass Yosemite in sheer scenic magnificence, and it was easy to see why. One wanted to linger in this sheltering desert Eden, a place that seemed set apart from the outside world.

. . . .

Zion Canyon first received significant national attention in 1904, when Frederick Dellenbaugh, who had joined Major Powell’s second Colorado River expedition at the age of seventeen as an artist and assistant topographer, published an article titled “A New Valley of Wonders” in Scribner’s Magazine. Dellenbaugh had visited the Mukuntuweap with the Powell Survey in 1876 but did not return until 1903. That spring he and two companions drove a covered wagon up the Virgin River past the villages of Virgin City, Grafton, and Rockville, savoring the grand procession of cliffs and towers rising around them. Mount Kinesava, which he called the “Great Temple of the Virgin,” stood “unique, sublime, adamantine” above the river valley.

. . . .

Even with the growing interest in Zion Canyon, its first recognition as a federal reserve came by happenstance, after a group of ranchers living near the canyon asked the General Land Office to conduct a survey to identify parcels of public land for disposal. Undertaken in 1908, the survey was led by Leo Snow, a deputy GLO surveyor from St. George, and included Angus Woodbury, who was then working as a ranger on the Dixie National Forest (he would go on to become Zion National Park’s first naturalist and historian). Climbing to the high platform now known as Observation Point, they enjoyed views that, in Snow’s opinion, were surpassed only by those of the Grand Canyon. Snow recommended to his superiors in the Interior Department that the main canyon be designated as a national park, but Secretary Richard Ballinger opted for a national monument, which required no action by Congress. On July 31, 1909, President William Howard Taft signed a proclamation under the Antiquities Act establishing Mukuntuweap National Monument, Utah’s second such designation.

. . . .

No federal appropriations were made for the new monument in Zion Canyon, nor was a custodian appointed to watch over it. Agents of the General Land Office who came to inspect the monument had to lodge with local families and hire wagons to get there. Lacking a decent access road, Mukuntuweap languished out of the public’s view, awaiting the publicity and funding that only designation as a national park could bring. Still, its designation represented a change from a landscape of utility to one of wonder and enchantment--a bargain that most civic leaders in Utah were happy to make.

* * *

More than a century ago, the great canyon of the North Fork of the Virgin River spoke wonders to scientists, travelers, and local inhabitants alike. If their reasons for coming to this canyon differed, each found a unique splendor in its towering sandstone cliffs and fern-lined grottoes. Named Mukuntuweap by John Wesley Powell, and called Little Zion by its Latter-Day Saint settlers, the canyon’s walls enclosed scenes of intimate beauty. Graceful cottonwoods lined the river bottom, keeping the summer heat at bay, while delicate vegetation ringed dripping springs and plunge pools. Zion Canyon was said to surpass Yosemite in sheer scenic magnificence, and it was easy to see why. One wanted to linger in this sheltering desert Eden, a place that seemed set apart from the outside world.

. . . .

Zion Canyon first received significant national attention in 1904, when Frederick Dellenbaugh, who had joined Major Powell’s second Colorado River expedition at the age of seventeen as an artist and assistant topographer, published an article titled “A New Valley of Wonders” in Scribner’s Magazine. Dellenbaugh had visited the Mukuntuweap with the Powell Survey in 1876 but did not return until 1903. That spring he and two companions drove a covered wagon up the Virgin River past the villages of Virgin City, Grafton, and Rockville, savoring the grand procession of cliffs and towers rising around them. Mount Kinesava, which he called the “Great Temple of the Virgin,” stood “unique, sublime, adamantine” above the river valley.

. . . .

Even with the growing interest in Zion Canyon, its first recognition as a federal reserve came by happenstance, after a group of ranchers living near the canyon asked the General Land Office to conduct a survey to identify parcels of public land for disposal. Undertaken in 1908, the survey was led by Leo Snow, a deputy GLO surveyor from St. George, and included Angus Woodbury, who was then working as a ranger on the Dixie National Forest (he would go on to become Zion National Park’s first naturalist and historian). Climbing to the high platform now known as Observation Point, they enjoyed views that, in Snow’s opinion, were surpassed only by those of the Grand Canyon. Snow recommended to his superiors in the Interior Department that the main canyon be designated as a national park, but Secretary Richard Ballinger opted for a national monument, which required no action by Congress. On July 31, 1909, President William Howard Taft signed a proclamation under the Antiquities Act establishing Mukuntuweap National Monument, Utah’s second such designation.

. . . .

No federal appropriations were made for the new monument in Zion Canyon, nor was a custodian appointed to watch over it. Agents of the General Land Office who came to inspect the monument had to lodge with local families and hire wagons to get there. Lacking a decent access road, Mukuntuweap languished out of the public’s view, awaiting the publicity and funding that only designation as a national park could bring. Still, its designation represented a change from a landscape of utility to one of wonder and enchantment--a bargain that most civic leaders in Utah were happy to make.

* * *