Occasional essays on the Western landscape

Canyon Sojourn

Frederick H. Swanson

Frederick H. Swanson

Photo: Utah Dept. of Transportation

Photo: Utah Dept. of Transportation

Here in the urban Wasatch Front, winter will often bring weeks of smoggy grayness in which the air we breathe attacks the lungs and depresses the spirit. When spring finally arrives, my thoughts inevitably turn toward the red rock canyons of southeastern Utah, far from urban congestion in both miles and spirit. A couple years ago, sometime in late March, I got to thinking of a certain canyon which I had not seen for a long time. A return visit was called for, so I loaded my truck with the usual camping gear and set off onto the surging freeway, headed for one small and not very well-known part of the Colorado Plateau Province. This is my account of that trip, in which I ask myself the question, where do I belong?

I have been seeking out wild places on our public lands since I was old enough to drive, but only recently have I come to understand the glaring contradiction of spending hours on roads packed with speeding vehicles in order to find my place of peace. But the expansive vistas and intimate canyons of the Colorado Plateau provide something I seem to need, and for this I’m willing to endure sixty miles of freeway driving and another hundred miles on rural highways to get to where the wind and the ravens supply the background sound. I want to linger on warm sandstone ledges, look up at the great cliffs, and let my thoughts wander where they will. I might also find a rock art panel mentioned in several guidebooks, which I missed on that first visit.

As I settle into a safe spot between two slower-moving trucks, I marvel at how the pace of our lives has accelerated during my lifetime. When I was a young adult I could drive down the highway at fifty-five or sixty, which was the most my wheezing VW could muster. Today at that speed I’d be a major hazard. Most passenger vehicles have four to five times the horsepower of my first cars, and the gigantic pickup trucks that are so popular here in the West boast even more. The sight of one of these behemoths closing up against my rear bumper fills me with dread, as much for our planet as my own safety.

Driving in this pack of supercharged vehicles demands absolute attention, and I force myself to ignore the flashing electronic billboards which have proliferated along our roadways in recent years. New lanes are continually being added to the freeway to accommodate the sharp increase in traffic, the result of rapid population growth along the Wasatch Front. Every few years our legislature ups the speed limit, which many drivers feel free to ignore anyway. I clearly do not belong in this frantic stream of metal and glass. Where are we all headed in our gasoline- and diesel-fueled rush? Some seem to revel in the power available to us, while others are just trying to keep up. I, for one, feel a need to drastically slow the pace of my life, but I’m sucked along in this relentless slipstream.

I have been seeking out wild places on our public lands since I was old enough to drive, but only recently have I come to understand the glaring contradiction of spending hours on roads packed with speeding vehicles in order to find my place of peace. But the expansive vistas and intimate canyons of the Colorado Plateau provide something I seem to need, and for this I’m willing to endure sixty miles of freeway driving and another hundred miles on rural highways to get to where the wind and the ravens supply the background sound. I want to linger on warm sandstone ledges, look up at the great cliffs, and let my thoughts wander where they will. I might also find a rock art panel mentioned in several guidebooks, which I missed on that first visit.

As I settle into a safe spot between two slower-moving trucks, I marvel at how the pace of our lives has accelerated during my lifetime. When I was a young adult I could drive down the highway at fifty-five or sixty, which was the most my wheezing VW could muster. Today at that speed I’d be a major hazard. Most passenger vehicles have four to five times the horsepower of my first cars, and the gigantic pickup trucks that are so popular here in the West boast even more. The sight of one of these behemoths closing up against my rear bumper fills me with dread, as much for our planet as my own safety.

Driving in this pack of supercharged vehicles demands absolute attention, and I force myself to ignore the flashing electronic billboards which have proliferated along our roadways in recent years. New lanes are continually being added to the freeway to accommodate the sharp increase in traffic, the result of rapid population growth along the Wasatch Front. Every few years our legislature ups the speed limit, which many drivers feel free to ignore anyway. I clearly do not belong in this frantic stream of metal and glass. Where are we all headed in our gasoline- and diesel-fueled rush? Some seem to revel in the power available to us, while others are just trying to keep up. I, for one, feel a need to drastically slow the pace of my life, but I’m sucked along in this relentless slipstream.

The freeway climbs a grade where it meets a promontory of the Wasatch Range, an old shoreline of Pleistocene Lake Bonneville. Here an enormous quarry is devouring the hillside for gravel and cobbles which were once washed by the waves of an inland sea. Rows of new homes are perched on a terrace that demarcates the lake’s highest level, looking like so many toy blocks arranged by some compulsive child. Off to the west, sprawling across the equivalent terrace, is a windowless, sinister-looking complex which houses part of our national security apparatus. The realization that we are all under its surveillance adds to the dull anxiety which pervades my body.

Much has changed along this urban corridor where I’ve lived for half of my life. What were once individual towns and small cities separated by farmland are now a continuous sprawl of tract homes, strip malls, and warehouse districts. Many of the surrounding hillslopes, which used to be covered with bunchgrass and sunflowers, have given way to housing developments and the campuses of Utah’s burgeoning tech sector. These glittering buildings bear inscrutable names which denote their cutting-edge purpose in the new digital world. The future may be virtual, but reality consists of an ever-expanding material culture, as if we were under the spell of some Ministry of Consumption that controls our every thought and action.

Much has changed along this urban corridor where I’ve lived for half of my life. What were once individual towns and small cities separated by farmland are now a continuous sprawl of tract homes, strip malls, and warehouse districts. Many of the surrounding hillslopes, which used to be covered with bunchgrass and sunflowers, have given way to housing developments and the campuses of Utah’s burgeoning tech sector. These glittering buildings bear inscrutable names which denote their cutting-edge purpose in the new digital world. The future may be virtual, but reality consists of an ever-expanding material culture, as if we were under the spell of some Ministry of Consumption that controls our every thought and action.

I drive on past the gun shops and motorsports dealers, the ten-acre lots filled with shiny new trucks and recreation rigs, drawn onward by the prospect of a few days of quiet and solitude in a relatively less-used corner of the desert Southwest. Once I’m down there, away from all this noise and rushing about, I hope to find a degree of clarity. I want to know what it might look like to live within limits, to forsake haste and excess in favor of a life that respects the bounds of a finite Earth. Visiting a place where humans accomplished this for more than a thousand years ago seems like a good start.

*

The traffic eases a little as I exit the freeway and head down a highway which cuts through the mountain front, taking my place amid a snaking column of long-distance freight haulers, recreationists heading to Moab, and all the other travelers bound for distant destinations. I’m following an ancient travel route between the Wasatch Range and the arid expanse of the Colorado Plateau, once used by the Nuche (or Ute) people and probably other indigenous groups before them. What used to take a week of hard walking now takes about two hours, thanks to the concentrated energy available to me at the pump. We have made straight a highway to the desert, but our God is a figure wrapped in speed and power, promising us the world in exchange for our fealty.

A rest area along this route has been set up as a kind of railroad museum, commemorating the tracks which were laid through these mountains in the 1880s. A plaque describes the family which once homesteaded this plot, whose members must have marveled at the advent of a form of transportation ten times as fast as horse and wagon. Today the route is used mainly for hauling freight, including unit trains of coal destined to be burned in power plants off to the west. Their steam turbines contribute to our overall standard of living as well as to the load of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere.

The highway crests a mountain summit and descends into Utah’s own coal mining district, situated beneath raw, broken cliffs which signify the northern edge of the Plateau Province. A small city lies beneath these cliffs, long tied to the mining industry but now diversifying into the recreational trade. I pass by more lots crammed with RVs and toy-hauler trailers. At a busy truck stop the owners of these rigs are filling up with liquid energy before venturing into the desert on their ATVs, UTVs, and dirt bikes.

Speeding along at a reasonably safe sixty-five, I keep to the right lane so that other vehicles can pass me. Sporty SUVs bearing mountain bikes and pop-up camping rigs rush past, as do the pickup trucks of the motorsport fraternity. Their trailers bear fear-evoking names such as Raptor, Sandstorm, and Vengeance. A complement of bus-length RVs are making the tour of the western national parks, and a few boaters are headed for what remains of Lake Powell. We are a people in motion, seeking pleasures not found in our cities.

The land opens out into a region of long vistas, where pinyon pine and juniper clothe the shale slopes. The scalloped escarpment of the Book Cliffs comes into view, marching off to the southeast toward the blue mesas, domed mountains, and hidden rivers of canyon country. It is a scene I have treasured for half a century, marking the entry into a landscape unlike any other on Earth.

Taking in this scene, I almost miss the turnoff for the dirt road that leads to my canyon destination. A modest wooden sign gives ambiguous directions and the map I’ve brought is of little help as the road winds through a confusing series of shale hills and low rims. I’m leaving the world of straight lines and set destinations for one that is defined by curvature, intricacy, and organic form. Bound inside my cage of steel, I sense that a different world awaits, and my hopes rise.

It is late afternoon when I pull into the primitive campsite at the mouth of the canyon. No one is around, so I park my truck and set off on foot to get the feel of the place. The cliffs which define this canyon rise abruptly from camp, promising views, so I head up the shaly, uneven slope. Picking my steps carefully, I try to summon reflexes dulled by too much walking on asphalt and concrete. The view gradually opens out over a thousand square miles of mostly uninhabited desert.

I’m standing at the edge of a great anticline formed when unseen forces deep within the earth bulged up layers of sedimentary rock, forming a gently curved dome. Flowing water has carved numerous canyons into this broad uplift, each taking a circuitous course down from the higher elevations to the west. They debouch into a long strike valley that runs perpendicular to the slope, forming the only linear feature in this crooked and undulating landscape. A power line follows this valley, its pylons marching in neat order off into the distance.

Traces of the Old Spanish Trail supposedly can be found here. To those who know where to look, they indicate where Mexican and Anglo drovers made the 2,700-mile-long journey between Santa Fe and Los Angeles. This must have been a long and tiresome passage, so the cottonwood trees growing in this side canyon would have been a welcome sight. The trail took a circuitous route around the heart of the canyon lands, unlike the interstate freeway that was punched directly through this broad uplift in the 1970s. The sound of tractor-trailers struggling up the long grade carries to me here, miles away on this rim. Despite this reminder of the civilization, I feel exhilaration rising in me. There is a sense of homecoming, although this is in no way my home.

I walk over to the cliff, which affords a vertiginous look into the canyon where I will spend the next few days. A small stream winds its way several hundred feet below, still white with ice where it runs under the shadowing walls. Shadows are overtaking the sere expanse to the east, so I head back down to the truck. These evening walks have been my ritual for as long as I can remember. With the last of the sun illuminating the distant Book Cliffs, I raise my hands to the sky in acceptance of its benediction.

Dinner is a simple dish of leftovers, heated on my propane camp stove on the tailgate. This will be my only use of fossil fuels during the couple of days I am here, and though it is not enough to compensate for the gasoline I burned to get here, the absence of most civilized comforts has its advantages—notably in the growing darkness and pervading quiet. Sirius appears off to the southwest, followed by a succession of other, familiar stars. I listen for any birds that may be about this early in the season, but all I hear are some cows which are browsing the sparse vegetation farther down the dry wash. The stress of the long drive begins to recede, and I contemplate the fact of my aloneness in this sea of stone and sage.

*

*

The traffic eases a little as I exit the freeway and head down a highway which cuts through the mountain front, taking my place amid a snaking column of long-distance freight haulers, recreationists heading to Moab, and all the other travelers bound for distant destinations. I’m following an ancient travel route between the Wasatch Range and the arid expanse of the Colorado Plateau, once used by the Nuche (or Ute) people and probably other indigenous groups before them. What used to take a week of hard walking now takes about two hours, thanks to the concentrated energy available to me at the pump. We have made straight a highway to the desert, but our God is a figure wrapped in speed and power, promising us the world in exchange for our fealty.

A rest area along this route has been set up as a kind of railroad museum, commemorating the tracks which were laid through these mountains in the 1880s. A plaque describes the family which once homesteaded this plot, whose members must have marveled at the advent of a form of transportation ten times as fast as horse and wagon. Today the route is used mainly for hauling freight, including unit trains of coal destined to be burned in power plants off to the west. Their steam turbines contribute to our overall standard of living as well as to the load of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere.

The highway crests a mountain summit and descends into Utah’s own coal mining district, situated beneath raw, broken cliffs which signify the northern edge of the Plateau Province. A small city lies beneath these cliffs, long tied to the mining industry but now diversifying into the recreational trade. I pass by more lots crammed with RVs and toy-hauler trailers. At a busy truck stop the owners of these rigs are filling up with liquid energy before venturing into the desert on their ATVs, UTVs, and dirt bikes.

Speeding along at a reasonably safe sixty-five, I keep to the right lane so that other vehicles can pass me. Sporty SUVs bearing mountain bikes and pop-up camping rigs rush past, as do the pickup trucks of the motorsport fraternity. Their trailers bear fear-evoking names such as Raptor, Sandstorm, and Vengeance. A complement of bus-length RVs are making the tour of the western national parks, and a few boaters are headed for what remains of Lake Powell. We are a people in motion, seeking pleasures not found in our cities.

The land opens out into a region of long vistas, where pinyon pine and juniper clothe the shale slopes. The scalloped escarpment of the Book Cliffs comes into view, marching off to the southeast toward the blue mesas, domed mountains, and hidden rivers of canyon country. It is a scene I have treasured for half a century, marking the entry into a landscape unlike any other on Earth.

Taking in this scene, I almost miss the turnoff for the dirt road that leads to my canyon destination. A modest wooden sign gives ambiguous directions and the map I’ve brought is of little help as the road winds through a confusing series of shale hills and low rims. I’m leaving the world of straight lines and set destinations for one that is defined by curvature, intricacy, and organic form. Bound inside my cage of steel, I sense that a different world awaits, and my hopes rise.

It is late afternoon when I pull into the primitive campsite at the mouth of the canyon. No one is around, so I park my truck and set off on foot to get the feel of the place. The cliffs which define this canyon rise abruptly from camp, promising views, so I head up the shaly, uneven slope. Picking my steps carefully, I try to summon reflexes dulled by too much walking on asphalt and concrete. The view gradually opens out over a thousand square miles of mostly uninhabited desert.

I’m standing at the edge of a great anticline formed when unseen forces deep within the earth bulged up layers of sedimentary rock, forming a gently curved dome. Flowing water has carved numerous canyons into this broad uplift, each taking a circuitous course down from the higher elevations to the west. They debouch into a long strike valley that runs perpendicular to the slope, forming the only linear feature in this crooked and undulating landscape. A power line follows this valley, its pylons marching in neat order off into the distance.

Traces of the Old Spanish Trail supposedly can be found here. To those who know where to look, they indicate where Mexican and Anglo drovers made the 2,700-mile-long journey between Santa Fe and Los Angeles. This must have been a long and tiresome passage, so the cottonwood trees growing in this side canyon would have been a welcome sight. The trail took a circuitous route around the heart of the canyon lands, unlike the interstate freeway that was punched directly through this broad uplift in the 1970s. The sound of tractor-trailers struggling up the long grade carries to me here, miles away on this rim. Despite this reminder of the civilization, I feel exhilaration rising in me. There is a sense of homecoming, although this is in no way my home.

I walk over to the cliff, which affords a vertiginous look into the canyon where I will spend the next few days. A small stream winds its way several hundred feet below, still white with ice where it runs under the shadowing walls. Shadows are overtaking the sere expanse to the east, so I head back down to the truck. These evening walks have been my ritual for as long as I can remember. With the last of the sun illuminating the distant Book Cliffs, I raise my hands to the sky in acceptance of its benediction.

Dinner is a simple dish of leftovers, heated on my propane camp stove on the tailgate. This will be my only use of fossil fuels during the couple of days I am here, and though it is not enough to compensate for the gasoline I burned to get here, the absence of most civilized comforts has its advantages—notably in the growing darkness and pervading quiet. Sirius appears off to the southwest, followed by a succession of other, familiar stars. I listen for any birds that may be about this early in the season, but all I hear are some cows which are browsing the sparse vegetation farther down the dry wash. The stress of the long drive begins to recede, and I contemplate the fact of my aloneness in this sea of stone and sage.

*

The next morning I set out under a crisp blue sky to see what I can recall of this canyon. Typical of the northern Colorado Plateau, it forms a deep incision in the uplifted and tilted deposits of wind-deposited sandstone, branching here and there and inviting exploration. A tiny stream describes a sinuous course as it meanders from one wall of the canyon to the other. In places it trickles along musically past sedges and willows, then drops into deep pools which centuries of floodwater have scooped out of solid rock. The largest of these is about the size of a hot tub and is filled with masses of bright-green algae.

Venerable cottonwood trees extend their twisted limbs over the stream. Still leafless this early in the season, their contorted trunks repeat the general curvature of this place. Some have fallen over and form great humps like shaggy prehistoric creatures. Buds are beginning to swell on a few of the living limbs and within a few weeks there will be a flutter of leaves all along the stream. It’s easy to imagine how early humans might have lived here. I search the sandstone walls for anything resembling a human mark, but can see nothing other than scratches and stains that belong to the rock itself.

Soon I come to the stream’s source in a cattail-filled marsh. The stony creek bed continues on for several miles, branching into a maze of side canyons. I choose one of these for investigation, but before long come to a dry waterfall. It is only about six feet high, and previous parties have stacked some rocks as an aid to climbing past it, but after a half-hearted attempt I give it up as too risky and turn back. The unknown no longer has as much hold on me as it used to, and the prospect of a relaxed afternoon back in camp beckons.

On the return leg I notice a used human-waste disposal bag that has been torn to bits by some rodent. The blue plastic appears wholly out of place here, and I shake my head at the half-hearted attempt to dispose of some shit. Yet all around me lie the droppings of cattle that have wandered up the watercourse as far as they could. Livestock, often considered emblematic of the West, have probably used this canyon for a century and a half. What belongs here and what doesn’t? It can be difficult to determine what is truly native to a place. Certainly I don’t fit into this environment, although it brings me a calmness I rarely experience in the city.

Back in camp, I get out a folding chair and take it down to the streamlet. Here I sit and read, shirtless, feet in the water, soaking in the afternoon sun. Looking up at the great cliffs, I speculate on what it would be like to live in this canyon, to find some way to enter into the flow of energy that animates the plant and animal life within its sheltering walls. How difficult would it be to flood-irrigate some crops, bag a rabbit or a wild turkey every few days, get to know which plants bear edible seeds and roots, and generally live in the manner of our distant ancestors? An idle fantasy, for I lack the skills to pursue any of these activities. But there is something seductive about the warmth and water found in this canyon. They rouse atavistic dreams and make me want to turn my back on the last hundred or so years of fossil-fuel-powered progress.

The matter is moot, anyway, since I am on public land that is not open to settlement. But I find the exercise useful as a way of probing the contrasts between earlier lifeways and our own. There is an undeniable attraction to the idea of living within the constraints imposed by soil, sunlight, and water, as difficult as that would be for us who rely on underground energy sources and all the material abundance that stems from their use. We have created an incomprehensibly intricate machine that manages, more or less, to keep nine billion of us alive--some with far more ease and comfort than others, and with a staggering cost to Earth’s nonhuman organisms. Yet our current state of affairs suggests that not far in the future, finding a simpler way of living that derives its sustenance more directly from the sun may not be an idle question.

The earliest humans who took on the challenge of living in Utah’s desert environment made a go of it for far longer than we moderns have. The Fremont culture, a somewhat loose-fitting term for the Indigenous people who occupied much of the northern Colorado Plateau and eastern Great Basin until about seven hundred years ago, were skilled agriculturalists and village-makers, but they did not necessarily confine themselves to a few central locations and could easily have incorporated a place such as this into their seasonal routines.

The still earlier inhabitants we call the Desert Archaic culture may also have passed through here and made use of the perennial water in this canyon. Even with primitive tools, these people could have channeled the little stream onto fields of maize, dug pithouses under the walls, or simply foraged and hunted for a short while before moving on. Some few among them desired to leave a record of their existence on a rock wall, markings which may or may not answer my questions of what it was like to live here.

It's so pleasant here by the stream that I decide to forego the truck tonight and sleep under the cliffs. I’m used to carrying a backpack for miles in order to gain the solitude I seek, but this early in the season it’s not easy to leave behind the conveniences. I’m getting soft in my old age, unable to get along without the inventions that have set us apart from the ancient and enduring world.

*

Venerable cottonwood trees extend their twisted limbs over the stream. Still leafless this early in the season, their contorted trunks repeat the general curvature of this place. Some have fallen over and form great humps like shaggy prehistoric creatures. Buds are beginning to swell on a few of the living limbs and within a few weeks there will be a flutter of leaves all along the stream. It’s easy to imagine how early humans might have lived here. I search the sandstone walls for anything resembling a human mark, but can see nothing other than scratches and stains that belong to the rock itself.

Soon I come to the stream’s source in a cattail-filled marsh. The stony creek bed continues on for several miles, branching into a maze of side canyons. I choose one of these for investigation, but before long come to a dry waterfall. It is only about six feet high, and previous parties have stacked some rocks as an aid to climbing past it, but after a half-hearted attempt I give it up as too risky and turn back. The unknown no longer has as much hold on me as it used to, and the prospect of a relaxed afternoon back in camp beckons.

On the return leg I notice a used human-waste disposal bag that has been torn to bits by some rodent. The blue plastic appears wholly out of place here, and I shake my head at the half-hearted attempt to dispose of some shit. Yet all around me lie the droppings of cattle that have wandered up the watercourse as far as they could. Livestock, often considered emblematic of the West, have probably used this canyon for a century and a half. What belongs here and what doesn’t? It can be difficult to determine what is truly native to a place. Certainly I don’t fit into this environment, although it brings me a calmness I rarely experience in the city.

Back in camp, I get out a folding chair and take it down to the streamlet. Here I sit and read, shirtless, feet in the water, soaking in the afternoon sun. Looking up at the great cliffs, I speculate on what it would be like to live in this canyon, to find some way to enter into the flow of energy that animates the plant and animal life within its sheltering walls. How difficult would it be to flood-irrigate some crops, bag a rabbit or a wild turkey every few days, get to know which plants bear edible seeds and roots, and generally live in the manner of our distant ancestors? An idle fantasy, for I lack the skills to pursue any of these activities. But there is something seductive about the warmth and water found in this canyon. They rouse atavistic dreams and make me want to turn my back on the last hundred or so years of fossil-fuel-powered progress.

The matter is moot, anyway, since I am on public land that is not open to settlement. But I find the exercise useful as a way of probing the contrasts between earlier lifeways and our own. There is an undeniable attraction to the idea of living within the constraints imposed by soil, sunlight, and water, as difficult as that would be for us who rely on underground energy sources and all the material abundance that stems from their use. We have created an incomprehensibly intricate machine that manages, more or less, to keep nine billion of us alive--some with far more ease and comfort than others, and with a staggering cost to Earth’s nonhuman organisms. Yet our current state of affairs suggests that not far in the future, finding a simpler way of living that derives its sustenance more directly from the sun may not be an idle question.

The earliest humans who took on the challenge of living in Utah’s desert environment made a go of it for far longer than we moderns have. The Fremont culture, a somewhat loose-fitting term for the Indigenous people who occupied much of the northern Colorado Plateau and eastern Great Basin until about seven hundred years ago, were skilled agriculturalists and village-makers, but they did not necessarily confine themselves to a few central locations and could easily have incorporated a place such as this into their seasonal routines.

The still earlier inhabitants we call the Desert Archaic culture may also have passed through here and made use of the perennial water in this canyon. Even with primitive tools, these people could have channeled the little stream onto fields of maize, dug pithouses under the walls, or simply foraged and hunted for a short while before moving on. Some few among them desired to leave a record of their existence on a rock wall, markings which may or may not answer my questions of what it was like to live here.

It's so pleasant here by the stream that I decide to forego the truck tonight and sleep under the cliffs. I’m used to carrying a backpack for miles in order to gain the solitude I seek, but this early in the season it’s not easy to leave behind the conveniences. I’m getting soft in my old age, unable to get along without the inventions that have set us apart from the ancient and enduring world.

*

On my second day in this canyon I set out to search for the rock art panel I’ve read about. There are precise directions to it on the Internet, but I prefer not to be guided by a satellite signal. It turns out to be much closer than I expect; a faint, rocky trail I’d breezed past the day before leads up to an immense overhang in the cliff, which looks like a possible site. I pick my way up through the crumbling talus and reach a thirty-foot expanse of smooth sandstone at the base of the cliff. Here are displayed a variety of figures and designs, some rendered in red and yellow ochre, others laboriously pecked into the rock. Most are faint, which is why I could not see them below. There are bighorn sheep with horns curling almost to their backs; deer or elk with elongated torsos and huge antlers; tall, looming anthropomorphs outfitted with headdresses or possibly halos. Other figures stretch out arms from which descend thin strips of red, suggesting rain. One creature looks like it is jumping rope.

In a particularly vivid tableau, a human figure raises a bow to take aim at a line of bighorns, one behind the other. I can only speculate on what the artist intended with such a scene—perhaps it shows successive hunts over a period of years. Whatever their purpose, these figures and designs must have held great significance for the people that made them. Their meanings are lost to us, however, just as it is clear that I cannot enter their world.

I turn away from the wall in order to survey this whole lower stretch of the canyon, with its tiny creek threading through a narrow riparian corridor. A flat-topped boulder provides a handy place to sit; I speculate that could have served as a workstand for these artists. Their creativity is astonishing, but these inscriptions do not answer my most basic question: what would it take to live in this place without relying on constant inputs of fossil energy? Or any place in the arid Southwest, for that matter?

It’s not clear whether the highly adaptable Fremont people managed a continuous presence in this little corner of the Colorado Plateau. The land base for agriculture is small, and the surrounding territory may not have held sufficient resources to sustain year-round living. More likely they showed up here seasonally, harvesting what they could from the land, then moving on. Their permanent villages appear in larger, better watered valleys elsewhere around the periphery of canyon country.

There’s also no indication that later Indigenous peoples of the region, principally Ute and Navajo, made much use of this canyon. Even the Mormon settlers of south-central Utah largely passed over this locality, although their livestock almost certainly wandered into this canyon. On my way in here I passed an abandoned pioneer homestead consisting of a tumbledown cabin made of cottonwood logs, a disused juniper-limb corral, and a root cellar buried in the nearby hillside. This family evidently obtained water from a spring at the base of a low cliff, now dry. Even when it was running, they must have led a difficult existence here.

Most of the Mormon occupiers of southern Utah stuck to well-watered localities along streams which issued from mountainous areas. Those who did venture into less hospitable territory, such as along the Paria or Dirty Devil rivers, often found their fields and homesteads washed away in savage floods. Today only a handful of scattered ranches and other tiny outposts remain within the interior of canyon country. Tourism, with its heavy reliance on fossil-fueled transportation, is now the major income producer. This is often promoted as a “sustainable” land use, but it relies totally on nonrenewable, and mostly very destructive, energy inputs.

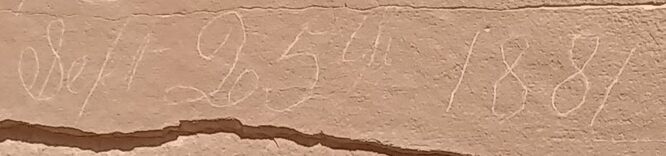

The Fremont, and to an extent the early Mormon settlers, appear to be the last cultural groups which were able to derive an existence from the immediate products of solar energy in the form of plants and animals. The Mormons depended to a degree on the products of industry back East, but it was not until late in the nineteenth century that they were able to forge real connections with the rest of the country. This event is commemorated in a date on the wall behind me: September 25, 1881, along with a name carved in tall, flowing letters. According to historical records, that was the year the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railway put laborers to work grading a bed for a line it planned to run through the open valley to the east. This fellow (his name is not important here) was probably involved with the venture in some capacity, perhaps as a camp cook or supervisor. He may have taken an hour to visit this spot and marvel at the earlier inscriptions. Whatever his role, he and his crew were the vanguard of a form of fast, linear transportation which relied on fossil fuel. Railroads would quickly displace the old subsistence ways and begin the transformation of the American West into the transient culture we know today.

In a particularly vivid tableau, a human figure raises a bow to take aim at a line of bighorns, one behind the other. I can only speculate on what the artist intended with such a scene—perhaps it shows successive hunts over a period of years. Whatever their purpose, these figures and designs must have held great significance for the people that made them. Their meanings are lost to us, however, just as it is clear that I cannot enter their world.

I turn away from the wall in order to survey this whole lower stretch of the canyon, with its tiny creek threading through a narrow riparian corridor. A flat-topped boulder provides a handy place to sit; I speculate that could have served as a workstand for these artists. Their creativity is astonishing, but these inscriptions do not answer my most basic question: what would it take to live in this place without relying on constant inputs of fossil energy? Or any place in the arid Southwest, for that matter?

It’s not clear whether the highly adaptable Fremont people managed a continuous presence in this little corner of the Colorado Plateau. The land base for agriculture is small, and the surrounding territory may not have held sufficient resources to sustain year-round living. More likely they showed up here seasonally, harvesting what they could from the land, then moving on. Their permanent villages appear in larger, better watered valleys elsewhere around the periphery of canyon country.

There’s also no indication that later Indigenous peoples of the region, principally Ute and Navajo, made much use of this canyon. Even the Mormon settlers of south-central Utah largely passed over this locality, although their livestock almost certainly wandered into this canyon. On my way in here I passed an abandoned pioneer homestead consisting of a tumbledown cabin made of cottonwood logs, a disused juniper-limb corral, and a root cellar buried in the nearby hillside. This family evidently obtained water from a spring at the base of a low cliff, now dry. Even when it was running, they must have led a difficult existence here.

Most of the Mormon occupiers of southern Utah stuck to well-watered localities along streams which issued from mountainous areas. Those who did venture into less hospitable territory, such as along the Paria or Dirty Devil rivers, often found their fields and homesteads washed away in savage floods. Today only a handful of scattered ranches and other tiny outposts remain within the interior of canyon country. Tourism, with its heavy reliance on fossil-fueled transportation, is now the major income producer. This is often promoted as a “sustainable” land use, but it relies totally on nonrenewable, and mostly very destructive, energy inputs.

The Fremont, and to an extent the early Mormon settlers, appear to be the last cultural groups which were able to derive an existence from the immediate products of solar energy in the form of plants and animals. The Mormons depended to a degree on the products of industry back East, but it was not until late in the nineteenth century that they were able to forge real connections with the rest of the country. This event is commemorated in a date on the wall behind me: September 25, 1881, along with a name carved in tall, flowing letters. According to historical records, that was the year the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railway put laborers to work grading a bed for a line it planned to run through the open valley to the east. This fellow (his name is not important here) was probably involved with the venture in some capacity, perhaps as a camp cook or supervisor. He may have taken an hour to visit this spot and marvel at the earlier inscriptions. Whatever his role, he and his crew were the vanguard of a form of fast, linear transportation which relied on fossil fuel. Railroads would quickly displace the old subsistence ways and begin the transformation of the American West into the transient culture we know today.

The D&RGW never laid rails on this route, instead choosing an alignment some miles to the east at the base of the 150-mile-long barrier of the Book Cliffs. When the line was finally completed near the town of Green River in 1883, transporting goods and people through this remote section of country suddenly became much easier. Locomotives picked up water and supplies of coal from mines at the base of the Book Cliffs before tackling the long grade over the mountains.

The coming of the rail line was a boon for Mormon cattlemen who had turned loose their stock to winter in these desiccated hills and greasewood-studded salt pans. All at once they were connected to regional and national markets in Denver or Chicago, making it possible to ship their cattle east for cash. This led to a sharp increase in grazing in the region, resulting in widespread overuse of the range. One can read historical reports of tall, abundant grass which was quickly converted to stubble throughout the unfenced range.

Livestock grazing appears to have triggered, or at least worsened, a cycle of arroyo cutting throughout the Southwest during 1880s and beyond. The high banks which border the lower reaches of this little canyon are suggestive of this erosion. Eventually the stream reached resistant sandstone and siltstone layers, but where it enters the open area to the east it dug ten or fifteen feet down, leaving steep cutbanks that trap tumbleweed--one of the hallmarks of degraded lands in the arid Southwest. Even pre-industrial agriculture can be unsustainable once the profit motive comes into play.

I’ve been sitting for some time at the foot of this sandstone wall, keeping warm in the morning sun, but I can find little here that points the way forward. The messages in the rock inscriptions were not meant for my eyes. The tableau before me is pleasing, but my fantasy of pursuing an agrarian existence here will remain just that. I wonder whether a place like this can even continue to exist in a world where power and speed are the watchwords. Part of this landscape was recently set aside as a wilderness area, which will limit development to some extent, and for that I am glad. Meanwhile our civilization will continue to subject nearly all of our planet to its heavy presence, while the very rich will prepare to colonize yet other spheres, using vast amounts of fossil energy to propel themselves and their expansionist, colonizing values into space.

Our society is not going to return to a hunting and foraging existing anytime soon, at least without being forced by some catastrophe to do so. Nor is it likely that significant numbers of us will adopt the small-scale, communitarian approach of the early-day Mormons, who despite their lack of ecological knowledge managed to create a working society in a harsh land. Our future appears destined to a high energy one, with the only question being how fast we can transition our sources of power to supposedly renewable ones. I do not look forward to the day when much of the Colorado Plateau and other American deserts are blanketed with solar and wind farms, with transmission lines marching across formerly open vistas. But at present, that is where we are headed.

What draws me to a place like this is the chance to spend time surrounded by living things; to enjoy clear, flowing water; to feel the wind and experience silence when there is no wind. This is not a place to indulge in atavistic dreams. A simple life close to the land is a project for elsewhere; this place ought to remain more or less as it is, an imperfect window into the past and a reminder of the beauty and order out of which our kind sprang.

This one small canyon exists outside of our linear, progressive, and exceptionally hurried way of seeing the world.

Meanwhile, American and world culture will continue to evolve toward some end we know not, as we seek and find ever-greater speed and power and pursue our limitless material acquisitions. But down here and in a few other wonderfully out-of-touch places, one can be reminded that it doesn’t always have to be so. That possibility remains in my heart as I climb down from my perch and return to camp, feeling alone but satisfied.

* * * to be continued * * *